“Ode to my Umi”: Celebrating Black Motherhood, Ancestry, and the Revolutionary Power of Rest

The newest exhibit in White Bear Center for the Arts’ Ford Family Gallery, “Ode to my Umi,” honors Black motherhood and ancestral wisdom. But the curator of the show, 2023-2024 Emerging Curators Institute Fellow Eshay Brantley, wants to make one thing clear: this exhibit is for everyone.

Directly influenced by the women in her family who have led each other through childbirth and hard times Eshay created “Ode to my Umi” as a place for Black people to rest. “Umi to me is an enlightened being, person, or woman who is continuously encouraging others and shedding light and wisdom on those around her,” Eshay says. “Black women care, love, and support everyone else, and hardly recognize the importance of doing it for themselves.” Being a young Black mother and oldest daughter of her generation before that, Eshay is familiar with the pressures and duties Black women feel towards others without an expectation to rest.

This mission translates to every artist and piece of artwork featured in the gallery. At the start of the curatorial process, Eshay broke the gallery up into three sections representing Mother, Grandmother, and Ancestor. Walking into the gallery, you step into the Grandmother section. This is represented by interdisciplinary folk artist Namir Fearce’s photographs of Eshay and her son, a baby mobile of hair combs and mirrors decorated with cowrie shells, and Namir’s experimental film, “my baby.” Grandmother represents the wisdom that comes with life lived. “She’s raised her own kids and faced things where she can guide Mother through and better connect to Ancestor,” Eshay said. Grandmother is also symbolic of the greater Black culture. Grandmothers play a vital role in preserving cultural traditions and passing knowledge down to younger generations whether it’s through doing hair, cooking, or storytelling.

The middle of the gallery space, the womb of it all, is Ancestor, made up of work from installation artist and designer Bayou Bay, and poetry from Donte Collins, the Inaugural Youth Poet Laureate of St. Paul. Anchored by the word ‘ANCESTOR’ painted in purple on the right wall, and surrounded by Bayou’s affirmation mirrors, the presence of Black heritage lives in the space. Personified in part by Bayou’s “Grandmother Coat,” a white windbreaker covered in patches stands next to a poem dedicated to his mother. Reflected across the ‘ANCESTOR’ wall is Donte Collins’ “Love Poem: Nocturn,” a sonnet in conversation with Annie Lee’s iconic portrait of a Black woman struggling to get out of bed on a Monday morning, “Blue Monday.” “Donte’s poem and ‘Blue Monday’ really show us how rest is revolutionary,” Eshay said. “Rest is love and care, rest is a warm blanket in winter, rest is okra stew on an empty belly. Rest is so necessary but we ignore it.” The chairs and benches in the space put that to practice for people to realize that rest doesn’t have to be the total surrender of sleep or lying down, but just being wherever your feet are.

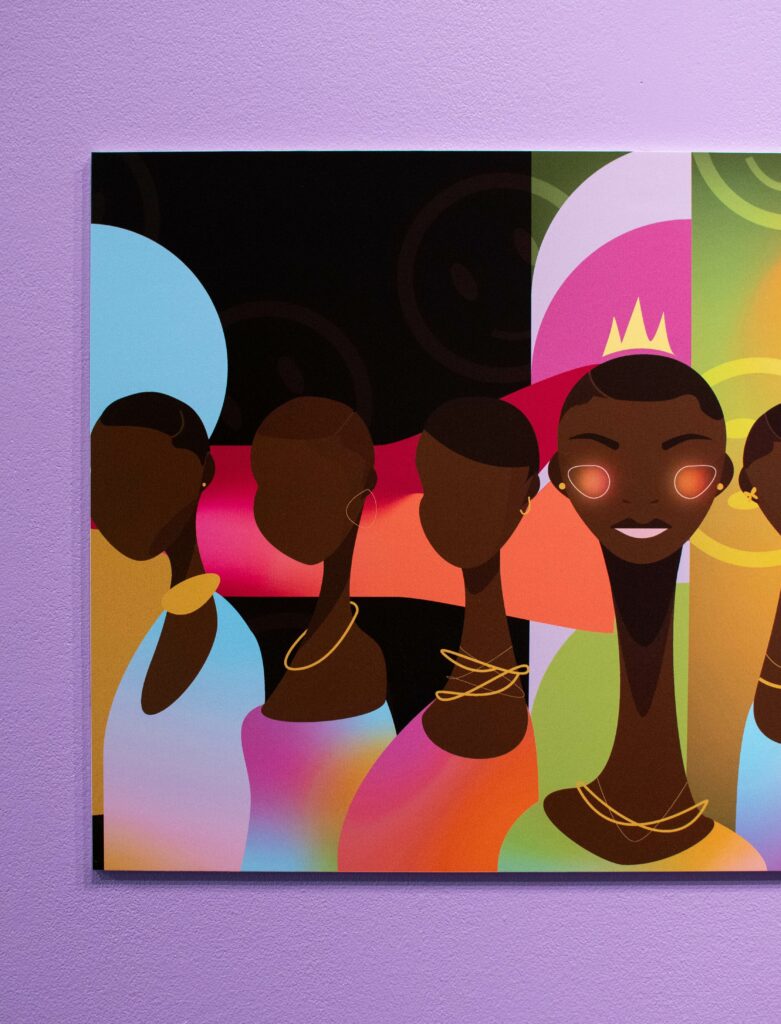

Traveling further into the gallery, the back purple wall houses Precious Wallace’s “My Them” collection. Precious is a self-taught graphic designer and one of the only female artists in the exhibit. “That was intentional,” Eshay said. In our patriarchal society, there are often expectations of women to cater to men. “I wanted to represent Black men who can also create a space for Black women and folks to be able to sit and just be.”

Precious’s work is representative of Mother. Her vibrant pop-art prints take on this fierceness and boldness that is often required of Black women in the world. One piece in particular stands out to Eshay. The piece “My Them” hangs on a standalone wall illustrating a woman facing forward with rows of women behind her. “This feels like my life,” she said. “Oftentimes I can switch this woman out for any woman in my family and I know there is a row of women behind her.”

“Ode to my Umi” is largely made for Black women to find a safe space of rest, where nothing is expected from them, and to see themselves reflected in the work. “Ode to my Umi” still exists for everybody, because as Eshay sees it, everyone benefits from Umi. “Everyone benefits from her as a secretary, as a friend, as a nanny, as a house cleaner. Black women have shaped a lot of things in American culture and a lot of the time, her praise goes unnoticed.” There can be those who come into the gallery and say “This isn’t made for me.” Or ask, “Why was I excluded?” Or, it can be a place to say, “What can I learn here?” Ask yourselves, what does it feel to be amongst work that doesn’t center your identity? And though your identity isn’t being centered, how can you find yourself in it? The lesson is for everyone, step into the gallery and think of a Black woman you can pay homage to.”

“Ode to my Umi” is a partnership between Emerging Curators Institute and White Bear Center for the Arts. The exhibit is on display in WBCA’s Ford Family Gallery now through August 2.